Parma: Giacomo Rizzolatti, il neuroscienziato scopritore dei neuroni specchio. È nato nel 1937 a Kiev, in Ucraina, allora nell’Unione Sovietica, si è laureato a Pisa.

Nel 2011 il Corriere della Sera, in occasione del 150° anniversario dell’Unità d’Italia, ha incluso le scoperte di Rizzolatti tra le 10 prodotte dal genio degli scienziati italiani da ricordare nella storia d’Italia.

Roma, 27 marzo 2014 –

Lo scienziato italiano Giacomo Rizzolatti, Accademico dei Lincei, ha vinto, per le sue pionieristiche ricerche sulle funzioni superiori del cervello, The Brain Prize 2014. È la prima volta che questo premio viene assegnato a un italiano. Assieme con Rizzolatti sono stati premiati Trevor Robbins (inglese, per le sue scoperte sul deficit di attenzione e iperattività) e Stanislas Dehaene (francese, creatore di un software per il trattamento di bambini con difficoltà di apprendimento). Il Brain Prize è stato assegnato dalla Grete Lundbeck European Brain Research Prize Foundation per ricerche sui meccanismi del cervello alla base di funzioni umane complesse come la lettura, l’abilità di calcolo, la motivazione e la cognizione sociale, e per gli sforzi di comprensione dei disordini cognitivi e comportamentali. Il premio di un milione di euro sarà consegnato ai tre vincitori durante la cerimonia che si svolgerà il 1* maggio a Copenhagen.

Il prof. Giacomo Rizzolatti si è augurato che questo “prestigioso riconoscimento, che per la prima volta viene dato alla scienza italiana, possa essere di stimolo al nuovo governo e creare maggiore interesse per la ricerca e nuovo sostegno alle attività, superando la poca attenzione che attualmente c’è per la ricerca e incrementando anche la disponibilità di fondi”. Lo stesso Rizzolatti sta pensando di destinare una parte del suo premio ad una associazione che si occupa di neuroscienze.

Rizzolatti è professore emerito di Fisiologia dell’università di Parma e Direttore del centro Social and Motor Cognition dell’Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia (IIT). Con un gruppo di colleghi ha scoperto i ‘neuroni specchio’, che sono considerati fondamentali per la comprensione delle azioni e delle intenzioni degli altri. La scoperta dei neuroni specchio ha dato vita a un nuovo campo di ricerca nelle neuroscienze sociali ed elevato i livelli di comprensione di disordini come l’autismo. (Ndr: a Rizzolatti, incontrato nel suo laboratorio a Parma, era dedicata l’intervista di Giannella Channel che è risultato l’articolo più letto del 2013, LINK).

Il presidente della Fondazione, Povl Krogsgaard-Larsen, ha dichiarato “Siamo orgogliosi di insignire questi tre scienziati del Brain Prize 2014. La loro ricerca interessa un ampio spettro di questioni riguardanti le funzioni superiori del cervello. I tre vincitori si completano a vicenda; insieme formano un trio molto forte. Siamo lieti di assegnare il premio di quest’anno a scienziati che ci hanno dotati di una migliore consapevolezza e conoscenza e di un miglior trattamento dei disordini di natura comportamentale e cerebrale, che sono un grave fardello nella nostra società”.

A PROPOSITO

The Mirroring of Emotions:

Neuroscience and Art

Salvatore Giannella & Manuela Cuoghi* / SoloMosaico magazine**

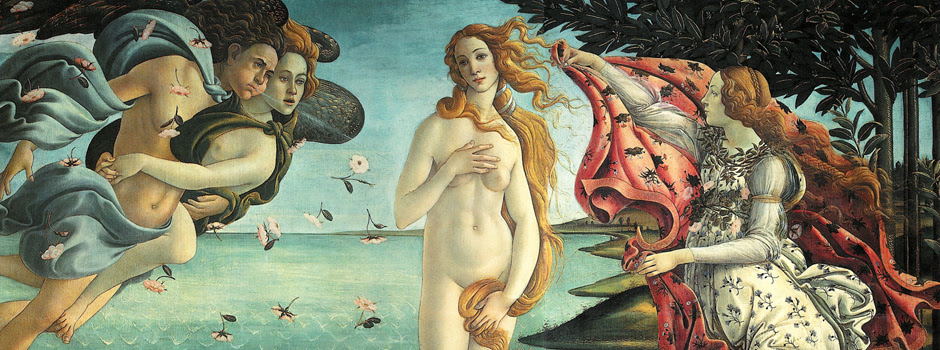

La Nascita di Venere è un dipinto a tempera su tela di lino (172 cm × 278 cm) di Sandro Botticelli, databile al 1482-1485 circa. Realizzata per la villa medicea di Castello, l’opera d’arte è attualmente conservata nella Galleria degli Uffizi a Firenze.

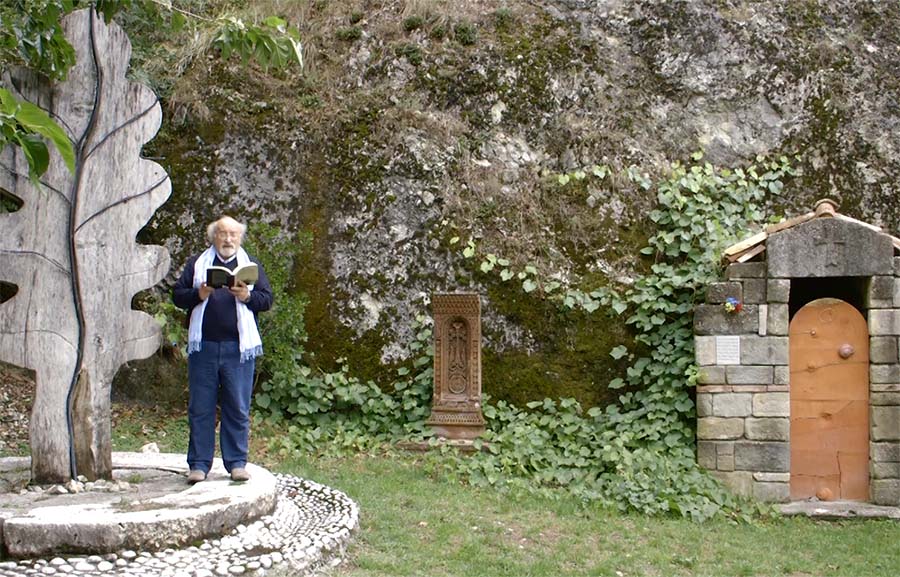

How are we able to decide if a work of art is beautiful or ugly? Or to evaluate whether we like a painting or sculpture? Why do we feel a sense of elation or profound emotion when in front of a work of art? And why do we say, “We do not explain art, we feel it?” To these ambitious questions, about which philosophers have debated for centuries without accord, the first scientific responses are now being offered by a group of researchers in the University of Parma Department of Neuroscience, under the direction of Professor Giacomo Rizzolatti. A 75-year old neurophysiologist who bears an impressive resemblance to Albert Einstein, Rizzolatti and his team have been studying for years the functioning of a particular area of the human brain involved not only in interpersonal communication, but in how we respond to the beauty of art.

One of the team’s fundamental discoveries regards the existence, within our neurological patrimony, of a particular class of cell called “mirror neurons.” To understand the importance of this discovery, it is valuable to note the concise assessment offered by Indian neuroscientist Vilayanur S.Ramachandra: “Mirror neurons will do for psychology what DNA did for biology”.

So what, exactly, do these mirror neurons do? Rizzolatti explains: “These nerve cells are activated by imitation – when we see someone else complete a certain act. If we look at someone drinking a fresh beer, for example, our brain is activated in the areas necessary to complete exactly that set of motions, even if we, in reality, are not doing so right then. There are some people who even feel the sensation of fresh beer in their mouth. In this way, the neurons reflect, like a mirror, that which they see in the mind of another”.

Let’s try to translate this description into metaphor: the neuroscientists of Parma have identified that in the garden of our hundreds of billions of neurons, there are some particular plants that will be stimulated by the activities of others. If watered by clean water, that is, by positive actions or by beauty, the mirror neurons will reflect this positivity. (Unfortunately, the opposite may also be true: we are thinking of the harm that is produced by so much violence and cruelty, spread through the media!).

But let’s remain in the area of positivity and enter into the great field of neurons and art. Rizzolatti explains: “To cast light on the relationship between mirror neurons and art, we conducted a series of experiments regarding sculpture. We took images of ancient Greek sculptures and, using an algorithm lent to us by a team of engineers, slightly modified the images by lengthening or shortening their otherwise harmonious proportions. We then showed these images to subjects during clinical testing and watched what happened in their brain using magnetic resonance equipment (MRI). First of all, we found that the original Greek works activated the mind much more than the modified images. But the most interesting thing is that they activated the areas of emotion, where there are mirror neurons of empathy (a word taken from a Greek root meaning to feel within). Thus, the mechanisms employed by the Greek sculptors are shown not only to activate the cerebral cortex and to fire up the nerve circuits, setting in motion millions of functions, but also to stimulate the emotional centers of the brain. We see definitively that art strengthens empathy in the person who looks at it, and can set in motion certain imitative processes by which beauty generates beauty”.

We sat down with Cinzia di Dio, a neuroscientist and collaborator of Professor Rizzolatti on this specific research, to deepen our understanding of the topic.

What defines the aesthetic experience?

CD: We all know that when we admire a work of art, we feel an almost visceral sensation of appreciation. Taking this shared experience as a starting point, our working group set out to study the moment in which a viewer feels that sense of enchantment. At that moment, our response is not a product of our conscious mind, influenced by factors like fashion, knowledge, common values attributed to an artwork or its monetary worth, but a more irrational emotion, a deep encounter into which we are thrust: the aesthetic experience.

How do we explain the aesthetic experience from a scientific point of view?

CD: One possible key is tied to the mechanisms of empathy, the state of mind or emotion that we feel when we know someone is suffering and suffer ourselves, or when we see someone laugh and feel happy, as well – in other words, when we enter into the emotional state of another by living those feelings ourselves, in the first person. From a scientific point of view, our understanding of the neural process that permits this empathy is still in an embryonic phase. All the same, one basic mechanism that has attracted particular attention in the last twenty years offers a physiological explanation to our capacity to empathize, and it is based on the properties of mirror neurons.

Would you reconstruct for me the journey of the Rizzolatti research team around this mysterious world of mirror neurons?

Around the 1990s, in the physiology laboratories of the University of Parma, Giacomo Rizzolatti and his research group, then composed of Vittorio Gallese, Luciano Fadiga and Leonardo Fogassi, discovered the existence of a particular class of neurons in the motor cortex of the monkey brain, subsequently known as “mirror neurons.” This “mirror system” – also studied successfully in humans – is activated both when we act and when we observe the actions of another person, putting us in a position to learn by imitating and to understand others based on their actions and behaviors. This capacity of ours to understand one another spontaneously, rather than rationally, is the fundamental basis of our ability to relate to one another, to empathize.

Why?

Through this mirror mechanism, which Vittorio Gallese defined as “bodily simulation,” we can read and experience visible elements in the behavior of others – their expressions, gestures, and actions – and automatically recall the emotional states associated with them. As Sigmund Freud expressed in 1921: “A path leads from identification by way of imitation to empathy, that is, to the comprehension of the mechanism by means of which we are enabled to take up any attitude at all towards another mental life.”[1]

Lead us by hand into the labyrinths of this process…

From an anatomical point of view, the connective bridge that translates our corporeal expressions (elaborated by the motor system) into emotional states (elaborated by the emotive system) and vice versa is an area of the brain called the “insular cortex,” or “insula,” named for its particular island shape. When this area of our brain “lights up”, the movements and expressions we observe in others tie in to our own emotions, allowing us to experience for ourselves their emotional state.

But how are empathy and the mirror system related to art and beauty?

One hypothesis is that, when something moves us and captures our attention with its beauty, such as the perfect form of classical sculpture (but this line of reasoning is valid even with regards to the beauty of a child or a flower), we enter into a state of motor resonance and of emotive empathy, which make us in some way live the physical and emotional expressions represented by the stimulus. In 2007, Giacomo Rizzolatti, Emiliano Macaluso and I showed just this mechanism. To capture the sensation that characterizes the aesthetic experience, and to understand how the brain responds to it, we showed young volunteers several images of classical and Renaissance figurative artwork – the Riace Bronzes, the Venus by Botticelli – while registering their brain activity via MRI. We chose classical and Renaissance images because their beauty is tied to certain parameters or proportions that reference an “ideal beauty”, incorruptible by time or negative sentiments. These parameters, if altered, render the same images less beautiful. Confronting the brain activity when the volunteers observe the sculptures that are beautiful (or, should we say, well proportioned) with those that are less beautiful (the ones that are less well proportioned), we discovered which areas of the brain light up to induce a sensation of aesthetic pleasure. When an artwork strikes us for its beauty, different areas of the brain are activated, some that analyze the physical structure of the stimulus image (the human body, in figurative artwork), others sensitive to movement (peculiar, if we think that these areas for movement are activated even when looking at immobile images!). All the same, the activation that struck us most of all was that of the insula, the same area that is activated when we live the emotional states of others. This discovery permits us to suggest that when we admire art that has intrinsic qualities of beauty – in the case of classical sculpture, qualities dictated by the perfection of its form – we can experience first-hand the emotional state or expression transmitted by that work, entering into a state of admiration that we call “aesthetic experience.”

The German philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, in The Dawn of Day, writes:

According to Rizzolatti’s studies, the well-devised work of art is in a position to evoke within us just this experience of imitation, catapulting us into the dimension of sensation and emotion.

- [1] Sigmund Freud, Group psychology and the analysis of the ego. (1921) 18:69–143, as quoted in, Vittorio Gallese, “Mirror Neurons and Intentional Attunement: Commentary on Olds,” http://www.apsa.org/portals/1/

docs/japa/541/gallese–pp.47- 57.pdf - [2] Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, The Dawn of Day, trans. John McFarland Kennedy (New York 1911), pp. 150-1: http://www.gutenberg.org/

files/39955/39955-h/39955-h. html

* Author: Salvatore Giannella, journalist and writer, has served as director for the weekly publication L’Europeo and the monthly magazine Genius, BBC History Italia and Airone (1986-1994). He has curated the culture and science pages of the weekly Oggi, and written books, and also documentary scripts for the Italian broadcasting network RAI (La Storia siamo noi). Since 2012, he has created and maintained the blog Giannella Channel. Manuela Cuoghi, his partner in life and work, had a brief career in graphic design, then was awarded a place teaching artistic education in the Italian public school system, where she has remained for more than thirty years.

** La rivista SoloMosaico, edizione da collezione in lingua inglese e russa, è dedicata all’arte musiva con riferimenti alla storia, alla contemporaneità e agli aspetti tecnologici di questo linguaggio artistico. Il fondatore del progetto è l’imprenditore russo Ismail Akhmetov, collezionista di opere d’arte a mosaico. Nel terzo millennio l’arte musiva sta conoscendo un nuovo rinascimento e Akhmetov ha risposto entusiasticamente a questo scenario accettando la sfida di promuovere ulteriormente una tradizione dal passato glorioso. Redattore capo della rivista è la ravennate Daniela Bravura che supervisiona e cura i progetti della Fondazione Akhmetov in Russia e a livello internazionale.